National Service in the Grenadier Guards, 1952-1954 (Caterham Guards Depot)

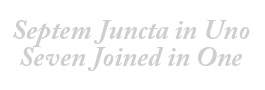

The call-up:

I was 18 years old in September 1952. About a week later I received a brown card through the post telling me that I should attend a medical.

The medical:

On the due date I had a chest X Ray at the Air Ministry in Gower Street, followed by a full medical at a military depot at Wanstead Flats. We recruits entered a large hall around which was a bench. In the centre of the hall was a long row of tables behind which were seated doctors in white coats. Having removed all our cloths which we left in a pile on one of the benches we passed down the hall to be inspected by each doctor. There must have been at least fifty of us standing there naked – one of the worst moments of my life. Yet another brown card arrived stating that I was completely fit.

Reporting for duty at Caterham:

A couple of weeks later I received yet another brown card instructing me to report to the Guards Depot at Caterham on the 6th November 1952, a date I will never forget. I was now a member of the Grenadier Guards. I was issued with all the army kit to start 12 weeks foot drill.

The uniform:

The whole of the British and Commonwealth armies wore the same battle dress, in action, on parade and for going on leave. National Service, Regulars and Territorials were all in the same army doing the same job. The only thing that differed was the head dress and the shoulder flashes, i.e. the name of regiment. (The Foot Guards wore – and still wear – Bearskins which were designed to protect the head from cavalry sword slashes, as the fur is attached to a wicker basket. The face is protected from sword slashes by a Curb Chain which hangs between the lower lip and the chin. Busbies are different; they are worn by the Horse Artillery and are shorter in height with the strap worn under the chin.)

For ‘fatigues’, i.e. menial duties like spud bashing, we would not wear a tie or gaiters.

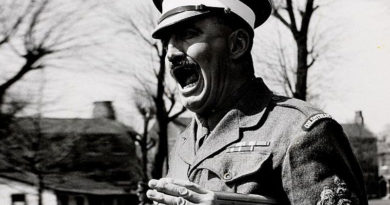

Foot drill:

The foot drill was hell on earth, chased from dawn to dusk. Eat, sleep, drill and bull shit was now my life. Upon reaching the required Guards standard there was our final inspection.

Weapons and battle training:

Then it was off to Pirbright for 8 weeks weapons training, followed by 2 weeks on the Yorkshire Moors for battle training with live rounds. During this period I took part in the 1953 Flood Disaster at Southend on Sea and Queen Mary’s funeral. It was the first time I had worn a bearskin in public. Then there was the Coronation.

We spend months training to kill people, yes kill people in cold blood. What other occupation does this?

Active service overseas:

After some leave it was off to Egypt by boat for what was active service, with as much sunshine as anyone could have wanted. For nine months we lived in a tent, with two nights on duty and two nights off. This was one place I was glad to get away from.

Here I was at the age of 18, being shot at and going out on patrol wondering if the next step I took would be my last because somebody had planted a land mine. It concentrates the mind. I slept in bed in full uniform with a loaded weapon strapped to my wrist, ready at a moment’s notice to defend myself. What civilian job compares with this?

The noise, the smell, the fear, this is now his way of life. Will it ever end. And when this hell on earth does come to an end we return to family, house and job and are expected to carry on as though nothing has happened.

Public Service in the UK:

Then it was back on a boat for a two-week trip to the UK, and Chelsea, London for public duties.

My first guard duty was at the Tower of London, which was followed by the Bank of England, then St James’s Palace and Buckingham Palace. By this time I had started to enjoy my time in the Guards. I was proud to walk down the street in my uniform, so much so that I am still a member of The Grenadier Guards Association. We meet once a month.

Demobilisation and the Territorial Army:

After serving full-time for two years, that was not the end. I had to do three years in the Territorial Army in the Middlesex Regiment. All my kit and uniform was kept at home, and I had to report for training, one evening per week, with 4 weekend camps per year and 2 weeks training each summer. So there were no summer holidays for 3 years, just army pay. This was camping under the stars, or under canvas, once in Essex, once in Thetford and once on Salisbury Plain, and it was in all weathers. The idea was to simulate an enemy invasion and how we would repulse them. The badge on our uniforms was the White Cliffs of Dover and in the event of the Russians rolling across Europe it would our task to defend all the counties inland from Dover. I was part of some 90,000 men who would be recalled to defend this one part of the southern counties. It was drummed into us that this was the last ditch defence. God help us if the Russians had got this far.

Once a Grenadier, always a Grenadier:

“Once a Grenadier always a Grenadier”. That is a regimental saying, meaning that, having served in the regiment you are a member to the day you pass on to glory.

The Brigade of Guards set the highest standards regarding good manners: always show respect, never be late, never make excuses and always be clean and tidy. All the male members of the Royal Family hold rank in the Brigade of Guards and set the standard to which we all aim for. It is not easy and sometimes not in fashion to maintain this way of life. It takes dedication and hard work.

NOTE: This article was ‘sourced’ from the internet at the link below to create content for the sites opening. The link for the original article is below.

https://www.1900s.org.uk/1949-1960-nat-service-gren-gds.htm#pagetop